Andrea Hope, 2018

Whilst the rock paintings, bark and body decorations of the Aborigines all testified to their close affinity with the land, the art of the early explorers demonstrated a need to understand and make sense of this strange new country.

The main purpose of early exploration, up until 1788 when the First Fleet arrived, was to seek trading opportunities, determine the resources of new lands (with a view to colonisation), survey and chart coastlines and undertake and record scientific research.

Sometimes professional artists were engaged, but on most occasions naval officers were trained in drawing and cartography and to develop their powers of observation - and it was they who not only mapped the routes they took, but also created a visual record of the ethnography, flora, fauna, geography and topography of the places they visited.

As Australia became colonised by the British, some sketches and paintings were also done simply for pleasure - from the early 17th century watercolour painting had been an acceptable aristocratic pastime, and from the mid 18th century the painting of landscapes, particularly topographic landscapes, had become popular with the middle classes.

A topographic landscape is almost like a map, that is, a clear conventional representation of a particular place. The viewer is presented with an apparently ordered and unambiguous landscape.

William Ellis, View of Adventure Bay, Van Diemen's Land, New Holland, 1777

This style of drawing had become part of the curriculum of military academies in order to achieve accurate visual records, such as coastal profiles for navigation purposes and the drawing of ports for naval intelligence.

It was never considered 'high art' but by the late 1700s topographic painting had been influenced the fashionable 'picturesque' style of painting in England, where the natural features of the landscape were arranged in a pleasing and irregular way, with the style being characterised by varied sinuous lines and variations in light and dark. Picturesque landscapes were linked to the fashion for travel and the exotic, so looking at paintings in this style became an aesthetic pursuit in itself.

You can see how the picturesque style quickly influenced early Australian artists. This oil painting, A direct north general view of Sydney Cove, attributed to Thomas Watling, is likely to have been painted in the early 1800s based on a 1794 drawing. 1.

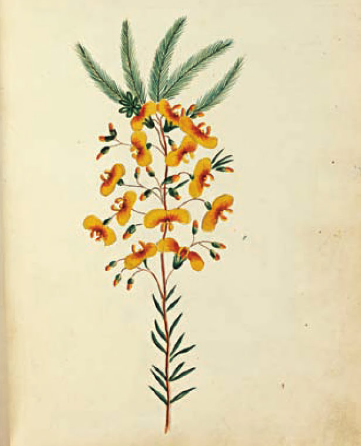

Artists often kept journals, or note books, which they would use to sketch on site. Very often, specimens of locals plants would also be collected and taken home so that they could be both displayed and copied in more detail. Sometimes live specimens survived the trip, however, once a plant had died, it lost its colour, so it was important that some record of the original colours was kept.

(Whilst not all drawings and paintings were always technically accurate or drawn in the traditional style of scientific illustration, there was generally enough information to allow experts in Britain to complete both the scientific recording, naming and illustration.) (see details in later blog)

Joseph Banks, a wealthy 25 year old naturalist, accompanied Captain James Cook on his first visit to Australia, and he brought with him two highly skilled topographical artists (see details in later blog). As a botanist Banks was highly interested in collecting and cataloging specimens of unknown plants.

As you will see as you look at the drawings and charts from the early explorers, watercolours used by naval chartmakers were generally limited to two greens, two browns, crimson, blue and black. Many of the artists of the time have used these few colours, combined with pencil and ink, to great effect.

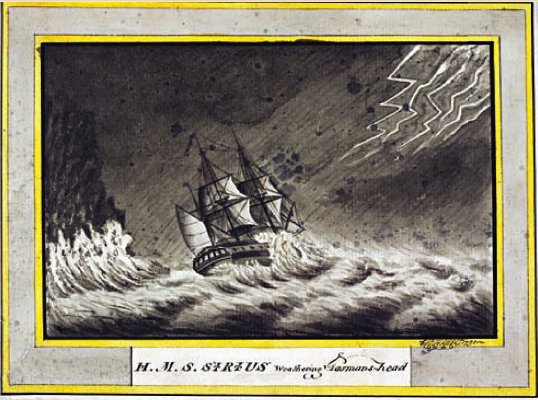

It was also customary for artists to draw black borders around their works, and charts in particular often had further borders of pink or cream wash around them, with the description of the subject written in the lower coloured border.

To recover some of the costs of the expeditions, drawings and painting were also commissioned which could later be sold individually or printed and included in a volume of work. Drawings were also sent 'home' as gifts, and prints were dedicated to patrons.

From the time of the First Fleet, the charts and drawing of views were sent to officials in England to show what the new colony looked like, and what progress was being made.

The best painters in watercolour produced suitable work for engraving, where a living and sometimes a fortune could be made. Artist John Lewin, who emigrated to Australia in 1800, was producing copper etchings by 1803.

Before the introduction of colour printing, most colouring was applied by hand. Aquatint was introduced in the 1770s as a way of using tonal technique to reproduce watercolour effects.

Lithography was invented in 1798, and this provided a much more flexible process as the artist could draw directly onto the stone, without needing either a separate drawing, or a specialist engraver.

Before the 1800s there was no form of printing (other than for government orders) undertaken within Australia. (see details in later blog)

There are also no recordings of oil paintings being produced in Australia until after John Lewin arrived. This is largely due to the fact that there was no way of satisfactorily transporting pigments and paints without them quickly drying out.

Scientific inventions which revolutionised the way in which artists were able to paint away for the studio largely occurred from the mid 1800s, although Reeves invented a 'paintbox' for watercolours in 1766 - but at considerable cost. George Raper, a midshipman on the Sirius in the First Fleet purchased a set - and this is obvious from the quality of his work. (see details in later blog)

Painting of people by early explorers prior to the 1790s was mostly limited to local aboriginals and naval officers, depicted in action. Portraiture became much more popular following settlement, and the availability of oil paints.

We now use the various collections and individual pictures that were sketched and painted by the early explorers as significant records of history, and they enrich the storytelling of our past. Without them, there would be much we do not understand, and information that would have been lost as the land was settled and denuded.

One example of an animal which is now extinct is the White Footed tree-rat, painted in the late 1700s. The last specimen near Sydney was recorded in 1845, however some sightings were reported in 1857 and perhaps as late as the 1930s.

And, because the purpose of art was to record and describe, we trust what we see.

Whilst acknowledging that many of our 'artists' from early expeditions did not have formal academic training, some of the paintings of our flora and fauna, in particular, are rich, luscious and beautiful, and form the basis of prints which are highly collectible today.

Key Sources:

McDonald, John, Art of Australia, Vol I, Exploration to Federation, Pan MacMillan, Sydney, 2000

Olsen, Penny, Feather and Brush: Three Centuries of Australian Bird Art, CSIRO, Collingwood, 2001.

Lisa Di Tommaso, Images of Nature, Natural History Museum, London, 2012

McCormick, Tim, First Views of Australia 1788-1825, A History of Early Sydney, David Ell Press, Chippendale, 1987.

Trove, Library of New South Wales,

1. National Library of Australia, National Treasures from Australia's Great Libraries, 2005, p24

Andrea Hope

Kiama NSW

2018